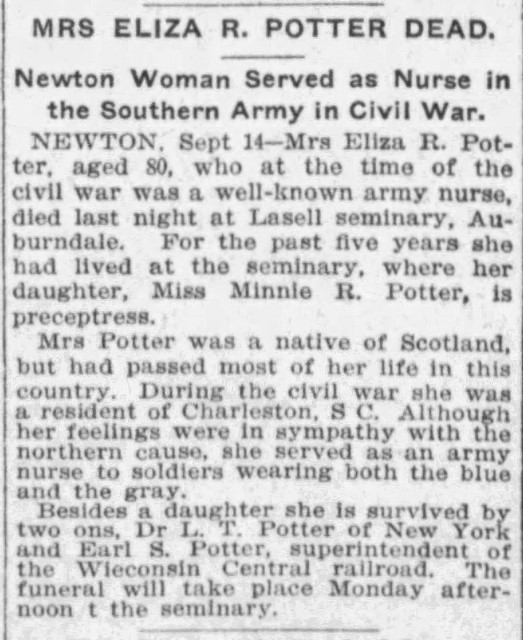

Mrs. Eliza Potter

Charleston, SC

Eliza was born Jan 1829 in Ireland, daughter of Alexander McGuffin. She was married second 9 Feb 1856 to Lorenzo T. Potter in Richmond Co., GA. Lorenzo was born 11 Jan 1818 in RI, the son of Earle H. & Hannah (Frothingham) Potter. Lorenzo died 5 Sept 1872 and is buried in Grace Church Cemetery, Providence, RI. Eliza died 13 Sept 1907 from Acute Indigestion at Auburndale, Middlesex Co., MA and is buried in Forest Hills Cemetery, Jamaica Plain, Suffolk Co., MA.

Famous Women Of The War by L. P. Brockett, M.D.,

Union Publishing House, New York, 1894, pages 95-110.

MRS. ELIZA POTTER.

In the whole history of the rebellion, so recently suppressed, there was nothing more deserving of our administration, nothing which appeals more strongly to our feelings of reverence for moral heroism, than the conduct of the few loyal women of the South. The number of persons of either sex, in any community, who have the moral courage to stand up in defiance of the sentiments and prejudices of the overwhelming majority of that community, especially on questions involving the rights and constitution of the State, when that majority are so frantic with rage and excitement as to be ready to put down any opposition by violence or murder, is very small. To maintain such a position of opposition for more than four years, when it involved complete isolation from society, constant obloquy and abuse, the loss of property, and the frequent peril of life, required a heroism to which comparatively few ever attain.

The loyal women of the South, solely from the love they bore to their country and its cause, endured all these trials and hardships. Personal, political, or pecuniary rewards they could not hope for; it was much if their lives were not the forfeit of their patriotism. Yet none made such sacrifices as they to minister to our sick and wounded soldiers, prisoners in the hands of the enemy.

It is to the work of one of the bravest and truest of these – a woman whose faithful and untiring labors have hitherto found no record save in the hearts of the thousands to whom she ministered, and in the book of God’s remembrance – that we propose to devote a little space and time.

Mrs. Eliza Potter was the daughter of Scottish parents of intelligence, piety, and worth, but herself born in the North of Ireland. She emigrated to this country when thirteen years of age, and after acquiring a good education was married while yet very young to Mr. Lorenzo T. Potter, a native of Providence, R. I., but then, as now, a merchant of Charleston, S. C. In that city Mrs. Potter has made her home for thirty years. Her husband, a man of high intelligence, enterprise, probity, and worth, occupied a leading position among the merchants of the Southern metropolis; and so great had been the services which he had rendered the city of his adoption, in the improvement of the streets, piers, and harbor, in the development of its resources and commerce, that he had more than once received the formal thanks of the city government for his public spirit and his labors for public good. His enterprises had been crowned with success, and when, in December, 1860, and city and State resolved upon Secession, Mr. Potter was one of the heaviest taxpayers of Charleston, his property being assessed at nearly half a million of dollars. In his family Mr. Potter was very happy. Of ten children who had blessed their union six were living, and all children of remarkable promise. His disposition was genial and gentle, but firm, and in his wife he had indeed a help-meet – one who could sympathize with him and sustain him in any season of sorrow or trial, and rejoice with him in his days of prosperity. Their ample fortune was not expended in personal or social display; theirs was a quiet, simple, unpretending home, but a large and noble hospitality was constantly maintained in it, and the poor, the sick, and the suffering had in Mrs. Potter a kind and judicious friend. In the epidemics of yellow fever, with which the city had been visited, Mrs. Potter had always considered it her duty to remain, and her skill and tenderness in nursing those who were attacked by the fearful disease were well known. These philanthropic labors, as well as the refinement, culture, and unaffected piety which were among the most beautiful traits of her character, had won for her a numerous circle of professed friends, and her home was constantly visited by the elite of Charleston society.

When the leaders of the rebellion, of which Charleston was the birth-place, began to talk of Secession, Mr. Potter was silent, but when his opinion was demanded avowed himself heartily and fully devoted to the National cause and the National flag. This avowal was very irritating to the leaders of the Secession movement; they had counted confidently on his calm, clear judgement, his lofty and upright character, and his wealth, as valuable accessions of strength to their cause, and they left no argument or inducement untried to gain his assent to their schemes. They represented to him the coming glories of the Southern Confederacy, when Charleston, instead of New York, should be the metropolis of the Atlantic coast, when weekly if not daily steamships should ply to the ports of England and France, and their great staple should rule the world, as it now ruled the United States. They offered him any post of honor or trust he might desire in the Confederacy; and knowing his thorough familiarity with the harbor (he having years before contracted for constructing the foundations of Fort Sumter), they proffered him the stupendous bribe of five thousand dollars a day if he would accompany a surveying party in making a tour of the harbor, and designate the points where torpedoes might be planted to prevent the approach of Union vessels to succor the already sorely-pressed garrison of Fort Sumter.

To all of these offers of honor or profit Mr. Potter had but one reply – that he loved his country and its flag, and that if he could not from his position serve it actively, at least he would not, under any circumstances or for any consideration, do or aid in doing anything which could injure it.

Finding all these inducements vain, they changed their tactics. They represented to him that he would be entirely alone, that in all Charleston there were not half a dozen men who were opposed to Secession (a statement not far from the truth), and that while it would be matter of regret to them to stand aloof from him, they should be compelled in duty to do so, and that it might be that much as he was honored he would expose himself by his contumacy to the vengeance of the military authorities, which would not respect even his eminent services in the past. It was all in vain. Gentle as he had always been deemed, the eternal hills were not firmer in their adherence to loyalty and truth than he. His wife was like-minded, but, as became her Scottish blood, more fearlessly and defiantly loyal than her husband. She had never been naturalized, and now, claiming British protection as being still a British subject, she prepared to do what she could to aid the North in the struggle which was so evidently approaching. That sweet, matronly face, from which twenty-five years of cares, sorrows, pains, anxieties, and joys had only mellowed and chastened the extraordinary beauty of its prime, now glowed with high and holy emotion as she dedicated her services thenceforth to the cause of her country and her God.

The year that followed was one of anxiety and depression. At first there was but little to be done except to watch and wait. Mrs. Potter, with wise prevision, prepared hospital stores against the time when they should be needed, but they were made to feel daily that the isolation to which they were doomed was growing more and more complete; those whom they had regarded as friends for years no longer visited them, and if they met them upon the street refused to recognize them. A few yet maintained a calling acquaintance, but even these availed themselves of this, for the most part, either to remonstrate with or to abuse them. The rebel General, Beauregard, evidently regarded them with suspicion, and, as they afterwards learned, set spies over them; and in every way they were made to feel that their loyalty was, in the eyes of the people of Charleston, a horrible offence. Meantime, intercourse with the North was almost wholly cut off, and they could only learn of any success on the part of the North by the added ferocity of the papers of the city. With that perverse tendency to bombast and rhodomontade which had always characterized the newspapers of Charleston, the Union troops were only spoken of as “the Vandal foe,” or sometimes, for short, “the Vans;” and bitter were the denunciations which were heaped on any one at the South who would show the least sympathy for them, even in misfortune. The defeat of the North at Bull Run was made the subject of the most frantic rejoicing, and the younger women manifested the greatest anxiety to obtain the bones of some of the Vandals to wear as trophies of their victory. The capture of Hilton Head, of Roanoke Island, and Newbern, on the contrary, filled them with rage, and no language was too bitter or violent to express their hate of the Union and of Union men.

Late in the autumn of 1861, a few Union prisoners, some of them wounded, were brought to Charleston, and Mrs. Potter, true to her principles, at once set about supplying them with needed comforts and ministering to them. She had the gratification of knowing that, owing in a good degree to her care, they were nearly all restored to their ranks in health and condition to do further service to their country.

Then followed a season of domestic affliction. Their eldest daughter [Julia], just at the age of dawning womanhood – a lovely, pious, and remarkably mature girl – was smitten with fever, and after several weeks’ illness, was taken from them. As she hovered on the verge of the spirit world, she seemed gifted with a prophetic view of the future, and while she bade her mother be of good cheer, for the clouds which now darkened the sky should surely be lifted, she asked most earnestly that a friend, one of the few who yet visited them, would come often to see her mother after she was gone, “for,” said she, “she will be very lonely in the trying time that is coming soon.”

In June, 1862, occurred the disastrous battle of James Island, in which the Union forces lost some four hundred or more prisoners, most of them wounded. These were brought into Charleston, and nothing could exceed the fury and hatred manifested toward them by nearly all classes of the white population of the city. Fair and delicately-nurtured women, who boasted of their superior refinement and culture, were ready to propose their murder in cold blood, and to express the hope that they would die of their wounds. All pity, all sympathy, all womanly tenderness seemed to have fled from the hearts of these furies. No sooner did Mrs. Potter learn of the arrival of these poor wounded prisoners than she determined to nurse and care for them. To do this was a matter of great difficulty. She was in delicate health, and the few quasi Union women who still maintained their intimacy with her protested strongly against her undertaking such a work in her condition; the military authorities had issued orders that no further attentions should be bestowed upon them than such as were necessary to prevent a pestilence, and the surgeon in charge was a rabid Secessionist, brutal and profane. The place assigned as a hospital for them was an old negro-pen and mart, long used for confinement and sale of slaves, with its kitchen and other outbuildings. There was no floor but earth, and it was a filthy and miserable den, into which any man of common humanity would have shrunk from thrusting a sick or wounded beast.

Mrs. Potter comprehended the situation at once. She saw that her only chance for accomplishing her purpose of ministering to those wounded soldiers must be through this rebel surgeon, and with skillful diplomacy she began to study the best method of influencing him. He had a mother in Charleston with whom she had had a slight acquaintance, though never hitherto a willing one. Now, however, she visited her with some presents of articles not readily procurable, and talked with her about her son. She soon found that he was ambitious of promotion, and was looking forward with some anxious longings to an appointment as surgeon of one of the large hospitals at Richmond. Here was something to work upon. Having ascertained at what time he would be at home, she returned and met him in the evening, and after listening to his ribald denunciation of the Vandals, asked to be allowed to visit the hospital as a matter of curiosity. He objected very strongly; said it was not a fit place for a lady to go to, “that the ------ rascals didn’t deserve any pity or attention; he wished he was rid of them, and he would be soon; he’d wing them.” By dint of urgency and more potent appliances, however, she obtained permission to visit the hospital the next morning. She had been forewarned that many of the men had been deprived of their clothing, “removed,” the surgeon said, “to get at their wounds,” but, in fact, stolen; and she had provided herself with portions of sheets and some hospital clothing, as well as cordials and such simple nourishment as could be most readily administered to them. A servant brought these to the foul den which the rebels had taken for a hospital, and Mrs. Potter and her son [Frederick], a noble, brave boy of fifteen, received them and entered the place. What an appalling sight met their eyes! Almost four hundred men suffering from wounds of every description, and, with hardly an exception, entirely nude, lay scattered over the filthy earth-floor, without blanket, mattrass, pillow, sheet, or even straw to rest upon; their wounds undressed, covered with flies and maggots, and tortured with thirst. The only attendants were the lowest dregs of the white population of the city, thieves and prostitutes taken from the slums or from the jails to wait on these poor fellows; and actuated by the same feelings as their superiors in station, they cursed the poor wounded men, jeered at and reviled them, and when compelled to furnish them with water or food, they took care that both should be as unpalatable as possible, and administered in such a way as to increase their sufferings.

Sending her son before her to lay gently on each mangled and suffering body a part of a sheet or other covering for its nakedness, Mrs. Potter advanced into the room and administered, so far as possible, cordials, soft custard, and other nourishment to the men, and washed and cleansed their wounds. In these ministrations of mercy she was constantly insulted and taunted by the vile wretches who were acting as professed attendants, and was told that “her white neck would get stretched if she went to do for them Vandals.” In the negro kitchen adjoining the main building she found a soldier from one of the Connecticut regiments, wounded in the head and shoulder, who had been thrown down with his head and neck resting in the ash-pit or fire-place of the kitchen; the oozing blood and the lukewarm water which had been thrown upon his wounds had made a lye with the ashes, which had eaten through a large portion of the skin of the neck and back of the head. She relieved him as far as possible, and having accomplished all she could that day, she set out for home, after arranging for another interview with the surgeon. She remonstrated with him in regard to the wretched condition of the wounded prisoners, but he declared that it was good enough for them, the ------ Vandals; it was better than they deserved. “That may be,” said Mrs. Potter, “but you cannot afford to have them left in that condition; you are looking for a promotion to a Richmond hospital, and you can only obtain it by proving that you know how to manage a hospital well. If, with all the difficulties in your way, you can make this a model hospital, you will have earned and will doubtless receive promotion.” He saw the reasonableness of this, but said that the Confederate authorities would not furnish him with the necessary hospital supplies to make it a good hospital. “I can help you in the matter,” said Mrs. Potter. “Appoint me a nurse in your hospital, and I will furnish you the necessary beds and bedding for the men, and such comforts and special articles of diet as they may need, and will perform a nurse’s duty beside; and very soon you can demonstrate your claim to a better position.” The surgeon objected to this, that she ought not to be brought into contact with such wretches as were then the nurses in the hospital. She replied that if she chose to take that risk he need not be anxious about it, and finally succeeded in obtaining from him the appointment, he drawing her pay and rations.

She entered upon her duties at once. In a factory of her husband’s, near Charleston, then closed, there were a large number of mattrasses which had been used by the hands. These she had brought to the hospital, furnished with suitable bedding, and she drew upon her home stores for the necessary hospital clothing as well as the food and delicacies needed. She endeavored to persuade the other nurses and attendants to wash the soiled clothing of the men, but they refused, and, whenever it was removed, destroyed it; and she was compelled to hire, at her own expense, the washing for all the patients in the hospital. She expended over eleven hundred dollars in this work alone. She dressed the wounds of the men herself, and with the aid of her son kept them cleanly and comfortable. This involved, in such a miserable and filthy place, a vast amount of labor – much of it of the most unpleasant character – but she never shrank from it; and in a short time that hospital was superior in neatness and comfort to any other in Charleston. The surgeon took all the glory himself. “This is the way I keep my hospital,” he would say to the rebel officers who visited him, and several times he was censured by the rebel authorities for suffering the “Vandals” to be so comfortable. Poor fellows! very little of their comfort was due to any kind offices of his. At times the old ferocity of his nature would gleam out, even in his intercourse with Mrs. Potter. One day, a soldier who had received some terrible wounds in the head, one of which had laid bare a portion of the brain, attracted her attention; the maggots, by hundreds, were crawling over his wounds, and he seemed to be suffering intensely. She carefully removed the loathsome creatures, washed his wounds tenderly, and laid cool, wet cloths upon them. He had not for some time previously shown any consciousness, but when she had completed her task he groped for her hands, and seizing them, cried out, “Mother! mother!” She was affected to tears by this; and as he still held her hands with a firm grasp, though seemingly dying or dead, she was compelled to wait a little before she could remove them.

The next day, as she came into the hospital, the surgeon said to her, “Oh, Mrs. Potter, I have something I want to show you. Come this way.” She followed him as he went to the dead-house, one of the miserable appendages of the hospital. Calling her attention to a rough box, he slipped off the cover and exposed the body of the poor sufferer, covered completely with maggots (its only covering), and said, with a sneering tone, “There’s your pet!”

Symptoms of scurvy began to make their appearance among the men, and finding it impossible to obtain a sufficiency of oranges, lemons, and limes in the Charleston market, Mrs. Potter sent to Nassau, N. P., for them, and ran the blockade repeatedly with her small ventures of tropical fruits. She made it a rule to refuse nothing to a wounded soldier which it was in her power to obtain, let the cost be what it might; and more than once, when tropical fruits were scarcest, and the Confederate currency seriously depreciated, she paid ten dollars each for oranges for her patients. Occasionally she brought them flowers, but the surgeon, partly perhaps at the prompting of other rebels, prohibited this, because it was giving aid and comfort to the enemy.

Mrs. Potter’s labors for the Union prisoners, though conducted quietly and as secretly as possible, drew down upon her scorn and spite of the rebels in every form which their malignity could devise. The fences and walls of her dwelling were constantly covered with abusive and obscene inscriptions, attacking alike her character and her motives. One of her servants found almost constant employment in effacing these evidences of petty smite. As she passed along the streets to and from the hospital, women of high social position, who a short time before had been proud of invitations to visit her, drew away their skirts as they passed her, lest they should be polluted by contact with a Union woman; and with nose uplifted and contemptuous shrugs, indicated their contempt for one who dared be a helper of wounded Union soldiers. The lower classes manifested their hate by the foulest and most abusive language.

Twice she was summoned to headquarters to answer to the serious charges of “giving aid and comfort to the enemy,” and of “shedding tears over the Vandal foe.” Her husband was repeatably questioned by the military authorities as to his wife’s giving so much help to the “Vandals;” but he replied always that his wife was a British subject, and therefore not responsible to them for what she did for these wounded men, and that she had resources of her own, which she expended without rendering him an account of them. He, meantime, in every way in his power, aided our soldiers who were in Southern prisons. His money bribed Confederate provost marshals to allow the transmission of supplies to Andersonville prisoners, when those supplies alone preserved them from a general starvation; his money and supplies reached the prisoners at Columbia and Florence, and mitigated, though it could not wholly prevent, the suffering there. The officers imprisoned under fire at Charleston were supplied with all necessary household utensils and food from his table; and those who escaped from the rebel prison found in him a protector, and were sheltered by his care for long periods – one of them for twenty-two months – till there was a feasible chance of escape. A truer-hearted patriot never lived than he.

The soldiers who had been wounded at James Island either died or recovered so far as to be deemed capable of removal to Columbia, Florence, or Salisbury; but others, captured in the siege of Fort Wagner, or on the ruins of Fort Sumter, or elsewhere on the coast, were sent to take their places, and Mrs. Potter found constant employment for her active charities. One incident in connection with the removal of the convalescent prisoners to Columbia is worthy of record. Knowing that at Columbia they would not in all probability find Union women to nurse them as tenderly as she had done, she devoted several days before their departure to instructing those who were most nearly recovered to care for the weaker and feebler prisoners, to dress their wounds, and give them nourishment. She had provided bundles of bandages and rags for dressings, and packages of crackers and bread for their journey. These she brought down to the hospital on the morning of their departure, intending to distribute them to them before they entered the ambulances; but their departure was hasted by the military authorities, and when she arrived they were all in the ambulances. Into each of those she threw a bundle of bandages, but while doing so was arrested by the guard, who charged her with giving the prisoners a means of escape. She explained; but they would listen to no explanation, and surrounded her with their bayonets, threatening her with instant death or with long imprisonment for what she had done; while outside, the howling mob were shouting, “Kill her! Shoot her! Hang her! She is a --------- Yankee! Run her through!” &c., &c. Mrs. Potter did not lose her self-possession, though she was aware of the danger she was in, but demanded to be taken to headquarters. At this moment the surgeon, who was to take charge of the prisoners en route to Columbia, rode up, and ascertaining the state of the case, ordered them to “disperse, and leave that woman alone.” The guard and the mob at their back, did not like to lose their victim so easily, and refused to release her until he should prove that he was really the surgeon in charge. When he had produced his commission, and the sergeant of the guard had made out the signature of the chief of staff, they sullenly drew back, and allowed her to escape.

But at this time, (the summer and autumn of 1863) there came to this patriotic family a still more painful and bitter experience of the malignity of the rebels of their city. We have already spoken of their eldest son, the companion of his mother in all her charitable labors, and her comforter in all her sorrows. He was a noble, manly, Christian boy, gentle and tender in his feelings, yet brave and firm in the maintenance of right. At the beginning of the war he had received from some friend the present of a Union flag. He prized it highly for the giver’s sake, but more highly as the emblem of the Union, and requested his mother to put it away for him till the time should come when it might again wave over a loyal city. He was a pupil in the Charleston High School, and was expecting to graduate there, and enter college in the autumn.

It had, somehow, come to the knowledge of some of the pupils of the high school, sons of some of the rebel aristocracy, that young Potter had this flag, and they demanded it of him, that they might trample on it and destroy it. He refused to surrender it. They threatened him with a whipping, but he was firm. Soon after h told his mother of their threats, and his determination not to give up the flag. She approved his resolution, and told him that he would not be first who had suffered for the flag of the nation. A few days later he came home and sent to his mother, to ask her to come to his room. He had been most cruelly beaten, and his back was covered with gory stripes, but he made no complaint, except to say, “I can bear this, mother, but I cannot bear to have them abuse you as they do.: “Their abuse does not injure me, my son,” was her reply; “our Master was reviled and evil-entreated, and why should not his servants suffer what he suffered?” The knowledge of this cruel outrage was kept from his father, who was at the time very anxious in regard to the condition of some of the Union soldiers, and who was also greatly harassed by the rebels. They young ruffians, when they found their victim determined not to yield, threatened to finish him next time. Mrs. Potter did not believe they would carry out their threat, but she took what precautions she could to prevent her son from being exposed to their malignity. It was, however, all in vain. He was to go to the high school to receive his diploma, before entering college, and when he came, these young villains laid in wait for him, and while one called his attention in another direction, the others set upon him, beat him on the head, and in a few minutes he was borne to his home, bleeding and insensible. He recovered his consciousness for a little time, conversed freely with his mother, of his hopes of heaven, his trust in Jesus, and his faith in the final triumph of the national cause. He acknowledged that he knew those who had assaulted him, but refused to give their names, and prayed for their forgiveness. Delirium soon supervened, and after some months of suffering, typhoid fever set in, and death came to relieve his poor bruised and mangled body from further distress. The mother, though at first almost overwhelmed at this terrible affliction, bore up under it with the patience and fortitude of a Christian. Rising from her sick bed, while this sorrow was yet fresh, she sought to relieve her overburdened heart by ministering to those who were suffering in the hospital. Never had her ministrations there been so gentle and tender, or her sympathies so hearty for those who had been wounded in defending the flag. Large numbers of those in the hospital at this time were very severely wounded, and sank under their wounds. To these she devoted herself especially, pointing them to the great Sacrifice for sin, and in many instances she was permitted to rejoice that they manifested evidence of having given their hearts to the Saviour before they parted.

The soldiers thus tenderly cared for, almost worshiped her. We have seen letters from several of those who survived and returned to the army or to their homes, so touching and earnest in their gratitude that their perusal would affect any reader to tears. The friends and families of the soldiers, at home, to whom, as often as opportunity could be found, she transmitted the dying messages and keepsakes entrusted to her charge, recognized with deepest thankfulness their indebtedness to her faithful care for these mementos of the heroic dead.

The cruelties inflicted on the wounded men by the rebel surgeons and attendants affected her deeply. On one occasion she had been moved by tears by some of their barbarities, and though, from fear of depressing the spirits of the men, she generally abstained from weeping in their presence, at this time she could not restrain herself, and shed tears as she performed her usual round of duties for the men. One poor fellow, severely wounded, was near death, and from him she received dying messages and endeavored to prepare him for his coming dissolution. As she left him, she dropped her handkerchief, and presently returned for it, when the dying soldier, looking up in her face, said beseechingly, “It was wet with your tears, lady; let me keep it on my heart till I die.”

There was, naturally enough, among the men an apprehension that their services and sacrifices for their country would be forgotten, and that when the struggle was over and peace had returned, none would remember even the names of those who had lain down their lives to secure the blessings of freedom. This fear Mrs. Potter earnestly combated. “If I live,” she said, “to see the return of peace, your deeds shall be recorded for your honor and the everlasting remembrance of the nation: if I die, I will bequeath it as a sacred trust to my children, to see that this work shall not be neglected.”

Peace came, but the war had swept away Mr. Potter’s large estate, except twenty thousand dollars which she had expended for the wounded and imprisoned soldiers, and about twice that sum which her husband had given for the same purpose. That, as given for a holy cause, they reckoned saved. But not for a moment did Mrs. Potter hesitate to fulfill her pledge to these dear soldiers of the Republic. A lot was secured in Magnolia Cemetery near Charleston; the Government have undertaken to fence it; the bodies of three hundred and thirty Union soldiers, who died in the prison hospitals of Charleston and were buried in the potter’s field of that city, are, this autumn, to be removed to their new resting-place; and partly from the wreck of her own fortune, and partly by personal effort among her friends, this heroic woman has procured the means for the completion of a shaft of ever-during granite, eighteen feet high, on which is inscribed the legend, IMMORTALITY TO HUNDREDS OF THE DEFENDERS OF AMERICAN LIBERTY AGAINST THE GREAT REBELLION, and with it the names of a hundred and seventy-one of these dead heroes, and a commemorative tribute to the unknown dead soldiers of the Union whose names it was not possible to ascertain. The record of these dead soldiers, imperfect as it is, is due entirely to Mrs. Potter’s solicitous care. The name of every soldier who entered the hospital, where it could be ascertained, was carefully entered by her, and copied by her daughter.

The nation’s gratitude is due to those who for the love of their country “jeoparded their lives even unto death, in the high places of the field;” to those, who in rebel prisons, foul, dank and loathsome, battled with starvation and fever, and often sank in the contest; is it not also due, and even in larger measure, to those, who, surrounded by rebels and exposed to all their malignity, suffered a perpetual martyrdom, while ministering to our sick and wounded men, and with no hope of reward, save in an approving conscience and the smile of God, gave their time, their substance, and their lives to the nation’s deliverance?

The Boston Globe, Saturday, Sept. 14, 1907